There’ssomething there

down

↓

Physicians have been aware of cancer for at least 4,500 years. The disease that was known for causing tumors to grow in the human body without any clear reason was given its name by Ancient Greek physicians about 2,400 years ago. Because the shape of some tumors reminded them of crustaceans, they derived its name from the Greek for ‘crab’. The growths were untreatable and when they broke through the skin they formed gruesome wounds. The first theory on the cause of cancer also dates to this era. It was thought that an excess of black bile led to an imbalance of the four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm), causing the deadly disease.

In the mid-19th century, cellular pathology replaced the ancient humoral pathology. Since then, cancer has been understood as a disease caused by the mutation of healthy cells. This “degeneration” first arises in one spot on the body and then spreads. The new understanding of the disease paved the way for modern oncology. It significantly improved the chances of survival for cancer patients, with healing becoming possible more and more often. The feelings that move us when we are confronted with cancer have also changed dramatically since then. This virtual exhibition focuses on this change and its effects.

Educating about Cancer

“Detected in time = curable”. This slogan was used in the 20th century as a way of promoting cancer prevention among German citizens. An essential prerequisite for the confident message was the significant improvement of surgical treatment methods for cancer in the late 19th century. For the first time, it was possible to surgically remove malignant tumors inside the body. If this could be done in time, according to the new understanding of the disease, there was a chance of saving the lives of people suffering from cancer.

Countless campaigns have now been organized to inform people about early detection techniques and cancer prevention. To motivate the population to behave in the desired way, the messaging always tried to appeal to their emotions. The feelings elicited for mobilization depended on several factors: The current medical and psychological understanding of cancer, any recent developments in cancer therapy as well as the changing ideals of society and contemporary morality.

Cancer leaflet

The educational pamphlet, written in 1911 by a Berlin physician, confronted readers with the prospect of an agonizing death. It was thought that this would motivate people to undergo early detection examinations. Critics, however, warned against distributing the fear-inciting pamphlet. By encouraging the constant search for barely recognizable symptoms of disease, the brochure creates a perpetual state of threat that could rob people of their zest for life.

Dr. Alfred Pinkuß / Zentralkomitee zur Erforschung und Bekämpfung der Krebskrankheit, 1911 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Photography: Exhibition section “Fighting cancer”

Beginning in 1930, Dresden’s German Hygiene Museum provided information about cancer in a permanent exhibition in an emphatically matter-of-fact manner. The exhibition organizers theorized that early detection examinations would be better promoted through hope for a cure than by stoking fear of the disease. They, therefore, emphasized the medical breakthroughs in cancer therapy. Side effects and complications of the treatments, on the other hand, were heavily minimized.

Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, ca. 1930 | Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden

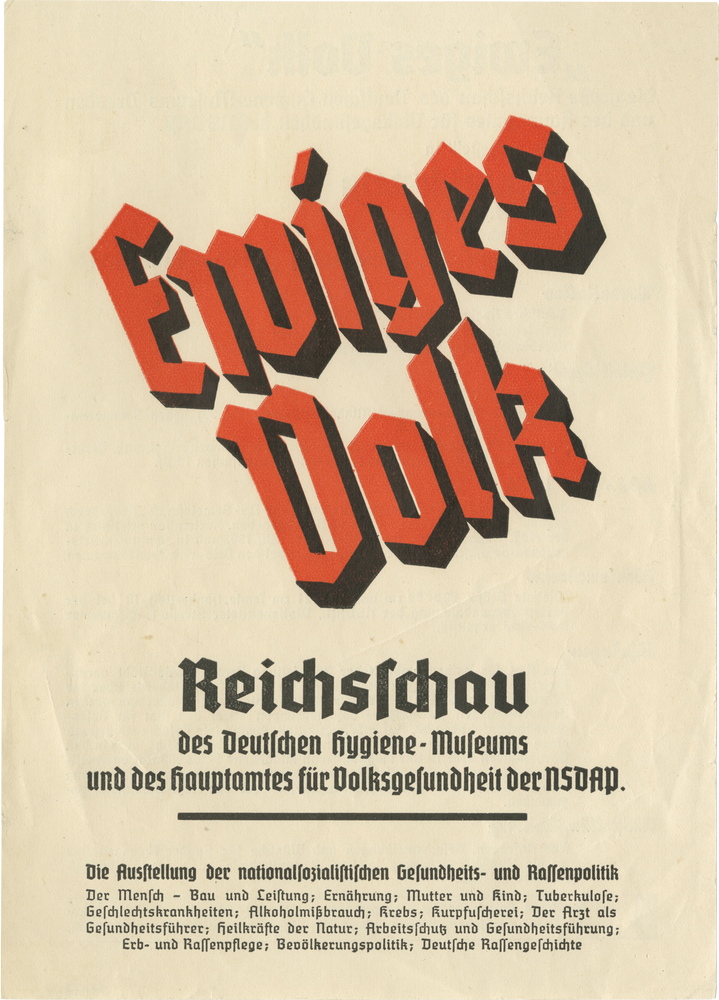

Flyer: Touring exhibition „Ewiges Volk“ (“Eternal people”)

In 1937, the German Hygiene Museum debuted its exhibition on health and racial policy; cancer was a central topic. The guidance to take advantage of early detection tests was bolstered in National Socialism with their calls for cancer prevention. Intensifying exercise and avoiding harmful stimulants were thought to be preventive. A fear of cancer was also said to be natural, but screenings were to be faced courageously, not avoided out of cowardice.

Deutsches Hygiene-Museum / Hauptamt für Volksgesundheit der NSDAP, 1937 | Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden

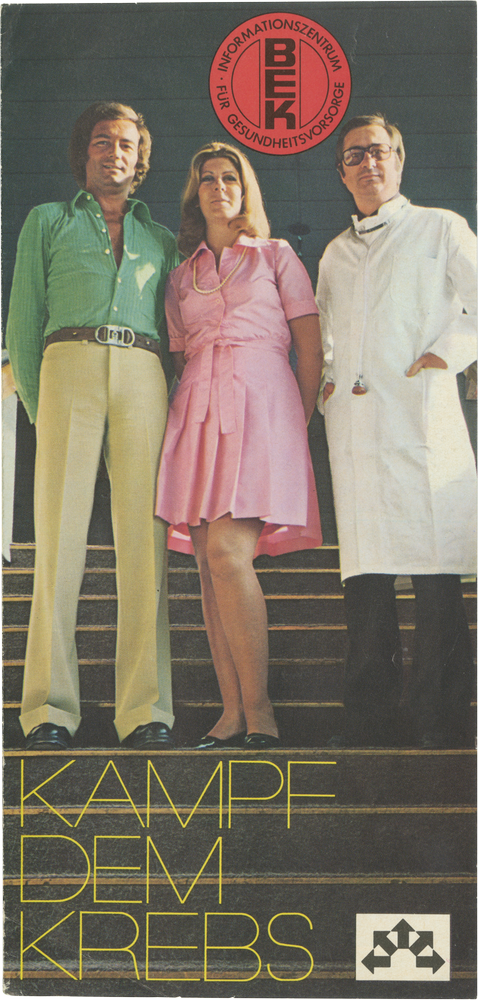

West German educational flyer

Published in 1973, the flyer might have seemed modern to German citizens: The front page shows confident faces, a doctor who no longer raises a reprimanding index finger, and the text avoids the moralizing tone that had once been common. It was written by the then-president of the Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft (German Cancer Society), the Essen oncologist Prof. Dr. Carl Gottfried Schmidt.

Barmer GEK Ersatzkasse, 1973 | Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden

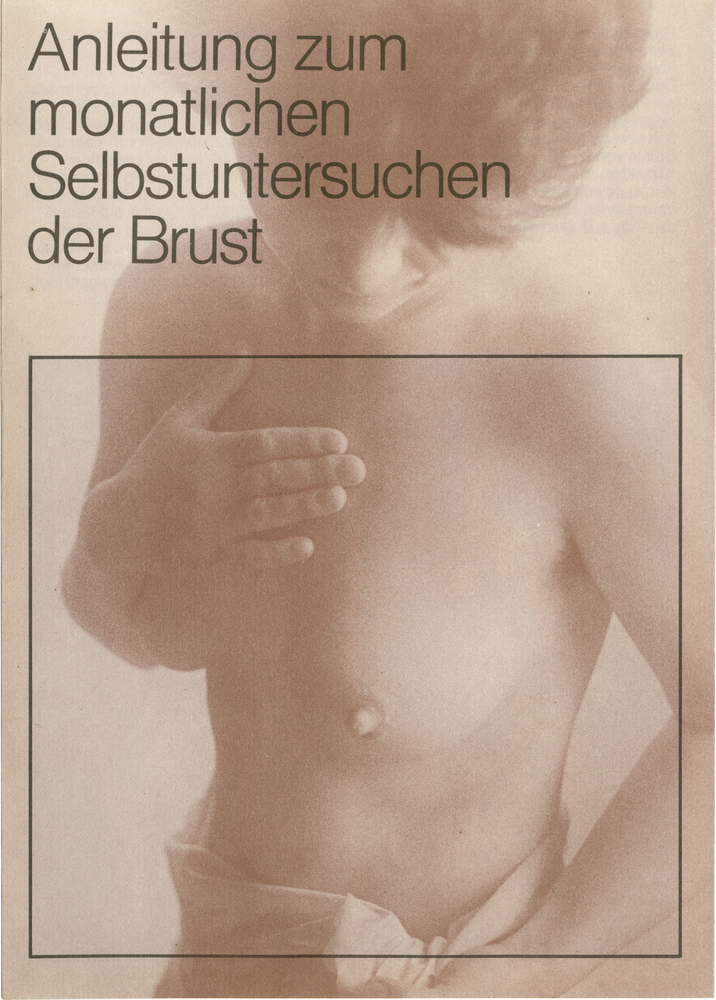

East German Informational Leaflet

The GDR had been distributing leaflets instructing women to examine their breasts since the 1950s. As seen here, the ideal of the informed, sensible woman was propagated early on; every woman was to be trained as her own “screening assistant.” Among other things, this was intended to alleviate the shortage in the GDR’s health care system and to cut costs.

Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden, 1988 | Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden

Various stickers

The stickers have a generally optimistic tone. While earlier anti-smoking campaigns were designed to stoke fear about the dangerous side effects, namely cancer, from the mid-1980s onwards casual slogans were used to encourage people, especially children and young adults, to refrain from smoking. Not smoking was cast in a flattering light and the emphasis was placed on the better quality of life that giving up smoking would bring.

Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, 1980er bis 1990er Jahre | Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V. (Sticker „mir stinkt’s“), um 2000 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

The “Cancer Personality”

Is there a connection between emotions and cancer? From antiquity to the 18th century, scholars explored the link between cancer and melancholy. However, in ancient times melancholy was understood in a different way. The term referred to multiform mind-body dysfunctions caused by black bile, the common symptom of which was anxiety, fear or sadness. With the 19th and 20th centuries came new assumptions about the body, psyche, and diseases (cancer) that would fundamentally change the perception of their connections to each other.

Around 1900, the theory that nervous exhaustion could cause cancer had gained traction. Picking up on psychoanalytical concepts, in the 1910s psychosomatic therapists began discussing the extent to which repressed troubles, unfulfilled desires or feelings of guilt could contribute to cancer. From the 1950s on, psychosomatic therapists suspected that people, especially women, with certain psychological characteristics (depressed, inhibited, submissive, incapable of authentic feelings) were more likely to develop cancer. Ultimately, the theory of the so-called “cancer personality” could not be empirically proven. Today within the field of oncology, this idea is considered a misconception.

Psychodiagnostics, text volume

In the 1910s, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach (1884-1922) developed a personality test. Participants were asked to interpret images formed by inkblots. Their interpretations were used to assess intelligence, emotional stability, empathy and perceptiveness. The “cancer personality” theory was essentially based on results from the Rorschach test, which was used in studies of cancer patients across numerous countries.

Hermann Rorschach, 1954 (7th edition) | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Psychodiagnostics, picture boards

The Rorschach test is still used from time to time in psycho-diagnostics: Participants are presented with ten panels of single- and multi-colored inkblots. While looking at the inkblots, psychologists observe, among other things, whether the boards are turned or held still, whether they interpret the patterns quickly or take their time, and they note which associations the pictures trigger. In order to preserve the conditions for the test, the inkblot pictures should not be released to the public.

Hermann Rorschach, 1954 (7th edition) | Berlin Medical History Museum of the Charité

Autobiographical report “Mars”

Fritz Zorn (1944-1976), a Swiss teacher, contracted lymphatic cancer at the age of 30. In his autobiographical report, the author describes his illness as the result of an emotionally cold bourgeois upbringing and an “unlived life” that was centered around conformity and success. The posthumously published report, which became a cult classic in the 1980s due to its social commentary, took up psychosomatic explanations of cancer and popularized the “cancer personality” concept.

Fritz Zorn, 1977 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Workshop report

In 1990, the Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid) organized a workshop during which scientists exchanged ideas about stress and immune mechanisms in patients with cancer. At this point, a change in the trend became apparent: The search for cancer-triggering psychological issues faded away, instead scientists asked about how emotions can be positively influenced during cancer therapy to help fortify patients.

Deutsche Krebshilfe, Workshop „Psychoneuroimmunology“, 1990 | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Talking about

cancer

In the 19th century, a cancer diagnosis was considered a horrific death sentence. Typically, patients were not informed of their cancer diagnosis. The knowledge of having cancer, doctors believed, would rob people of all hope, destroy their will to live and, therefore, shorten their remaining tolerable time. In the 20th century, the voices of those opposing this practice grew louder and louder. However, it was not until the 1980s that it became more common to notify patients of their diagnosis. Today, criticism is no longer centered around the decision of whether or not the diagnosis should be communicated, but rather targets how it should be communicated.

Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland

* 1762 in Langensalza,

† 1836 in Berlin

- Physician, royal personal physician, medical director of the Charité, social hygienist and popular educator

- Representative of the life force theory and founder of the “doctrine of long life” (macrobiotics)

“Is it not decided that fear, especially of death, anxiety, and terror are the most dangerous poisons and directly paralyze the vital force; and that hope and courage, on the other hand, are the greatest invigorators, often surpassing all medicines in power, indeed without which even the best remedies lose their power? The physician must, therefore, above all things, be invested in the preserving hope and courage of the sick, preferring to make the matter easy, to conceal all dangers […] To announce death is to give death, and this can never, must never be the business of one who is there purely to spread life.”

Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland, Enchiridion medicum oder Anleitung zur Medizinischen Praxis. Vermächtnis einer fünfzigjährigen Erfahrung, Berlin 1836.

Albert Moll

* 1862 in Lissa (today Leszno),

† 1939 in Berlin

- physician, psychiatrist, sexologist, sharp critic of contemporary human experiments

- advocated the communication of cancer diagnosis so that patients could give informed consent to interventions and therapies

“It may be difficult for the physician to inform the patient about the terminal nature of his suffering. It may be done in a gentle way, he may leave him a glimmer of hope, especially since he must consider that all knowledge and predictions have only a conditional validity […]. But the doctor, who was only asked for an expert opinion, must not tell a lie […]. In such a case, it is also unacceptable to give an ambiguous answer, which is supposed to hide the painful truth. […] It will be said that such behavior of the doctor is inhuman. On the other hand, I would like to note that informing the patient […] is also a medical and a human duty […].”

Albert Moll, Ärztliche Ethik. Die Pflichten des Arztes in allen Beziehungen seiner Thätigkeit, Stuttgart 1902.

Albert Krecke

* 1863 in Salzuflen,

† 1932 in München

- Surgeon, ship doctor and founder of a private clinic

- esteemed by Kurt Tucholsky for his kindness, operated on the sons of Katja and Thomas Mann, among many others

“Should we now tell a patient, who knows the poor chances of curing cancer, the true nature of his suffering and thus condemn him to a depressing hopelessness for the rest of his life? Some doctors say, ‘We must reveal to cancer patients the nature of their suffering because otherwise they cannot be persuaded to undergo the only proper treatment, surgery.’ […] It always seems to me a cruelty to try to force the sick person to have an operation by telling him that he is suffering from cancer. […] The majority of cancer patients come to the doctor so late that surgical treatment is no longer possible. […] How can we give these patients new hope every day, how can we lead them with firmness and confidence through the depths of their suffering and over their despair, this must be the most ardent concern of every true physician. […]”

Albert Krecke, Vom Arzt und seinen Kranken, München 1932.

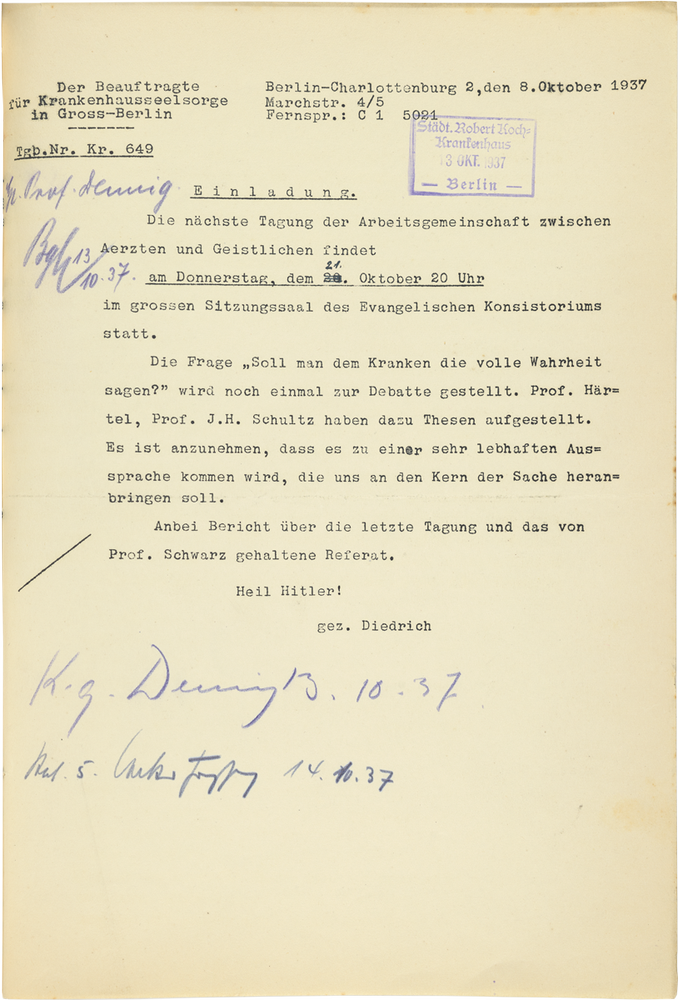

Johannes Heinrich Schultz

* 1884 in Göttingen † 1970 in West Berlin

- psychiatrist, psychotherapist, inventor of autogenic training

- advocated the murder of disabled people under National Socialism

“Today, the courage to tell the truth is one of the most important demands of our time. The new Germany wants courageous people who also have the courage to face the truth. The German man should not only be able to live courageously, but also to die courageously. Nevertheless, there will always be cases where it is not appropriate to tell the full truth, as in the case of children, the nervous, the hysterical, the mentally inferior, and so on. One will have to make one’s decision there on a case-by-case basis. “Dying people” and “dying people” are two different things. [...] In the case of unstable, inwardly fragile people, what is to be done will have to be decided between the doctor and pastor. Otherwise, the rule is that truthful behavior best secures the physician’s true authority over the sick and their relatives.”

Soll man dem Kranken die volle Wahrheit sagen? Tagung der Arbeitsgemeinschaft zwischen Ärzten und Geistlichen am 2.9.1937. LAB Berlin A Rep. 003-04-03, Nr. 55.

H. D. Claus

(no life data, no portraits known)

- Radiologist

- Chief physician of the Radiation Institute at the Erlabrunn Miners’ Hospital in the Ore Mountains

“Every experienced tumor therapist will confirm, however, that to live through weeks and months of uncertainty as to the existence of a tumor, a recurrence, or metastases, to evasively answer often repeated, appropriate questions, is tantamount to a mental terror in an intelligent patient who keeps a close watch on suspicious changes in his body, the damage of which may be incomparably greater than the shock which an appropriate communication of the presence of a malignant tumor is likely to produce. If one tries to deceive the patient about this with transparent phrases, a tension of distrust and insincerity arises between doctor and patient, which has a conceivably unfavorable effect on the behavior and attitude of the sick person towards the doctor, nursing staff and other patients […].”

H. D. Claus, Zu einigen praktischen Fragen der Metaphylaxe nach Strahlentherapie der Geschwulstleiden, in: Das deutsche Gesundheitswesen 17 (1962), 35, S. 1489-1498.

Hildegard Frieda Albertine Knef

* 1925 in Ulm † 2002 in Berlin

- actress, chanson singer, author

- learned in 1975 that she had breast cancer, wrote a novel about her illness

“The faces of my baker’s clerks had been contrite. […] ‘It is …,’ one spoke, breaking off as if, after wading through the first and second acts, he had discovered the nightmarish text hole from which there is no escape. ‘It is …’ he began again, bravely and pitifully. But I, as the imperiously frightened leading role bearer, let hear: ‘Tell the truth, I demand the truth.’ […] Now they nodded, as if I had taken over the saving work of the failing prompter, as if I had given the signal, set the course of memory. ‘The frozen section was suspicious,’ came fluidly, the sentence sure. And the second: ‘I went to the lab, the last test confirmed it.’ Now a cough, a long-drawn-out ‘yes’ muddled follows: ‘It’s a carcinoma, cherry-sized.’ […] The verdict was in.”

Hildegard Knef, Das Urteil oder Der Gegenmensch, Wien u.a. 1975.

Fritz Meerwein

* 1922 in Basel † 1989 in Heidelberg

- psychiatrist and psychoanalyst

- important pioneer of psycho-oncology

“The physician’s full duty to inform, which is desired by most sick persons, has contributed considerably to reducing the danger of under- and mis-information of patients at this stage. […] In a second consultation scheduled shortly after the initial information, the patient should usually be given the opportunity to discuss fears, anxieties, and fantasies, […] in detail with the first treating physician. […] If the duty to inform is handled carefully, the contact between patient and physician usually develops openly and truthfully in the initial stage. Under the impression of the measures to be initiated now and the explanation of the therapy options and goals by the physician, the patient can often well overcome the initial shock and the psychological sense of isolation and doom that the diagnosis ‘cancer’ has triggered in him.”

Fritz Meerwein, Die Arzt-Patientenbeziehung des Krebskranken, in: ders. (Hg.), Einführung in die Psycho-Onkologie, Bern u. a. 1981, S. 84-165.

Experiencing the transition

When receiving a cancer diagnosis in the 20th century, people entered a new realm of existence. Most patients remained in the hospital for some time; immersed in foreign surroundings with a very peculiar atmosphere. Unfamiliar daily routines and unusual rules dictated their everyday life. They became newly acquainted with the fundamental dynamics of dependence. Above all, however, they suffered serious interventions on their bodies. For most of them, the treatments were accompanied by unprecedented pain, never-before-experienced states of exhaustion, stress, and loss of control. This describes the experience that many cancer patients continue to go through today.

Nevertheless, the experiences of cancer patients are ever-changing: New knowledge about cancer, innovations in therapy, a changing relationship between nurses, physicians and patients, along with the general removal of taboos about cancer are all shaping the conditions under which the disease is endured and suffered. That experiences of illness depend on how people encounter the illness itself is a relatively new, but also controversial idea, popularized in the late 1970s.

Guidebooks

In the 1980s, Mildred Scheel published relevant cancer guidebooks. The doctor was a committed advocate of openly discussing cancer and made a significant contribution to removing the taboos surrounding it. As the wife of the then German President, Walter Scheel, she founded the Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid) in 1974, an organization that supports patients and their families in many ways while also promoting cancer research.

Mildred Scheel / Jochen Aumiller, 1982 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Blue Guidebooks

Since the 1990s, the German Cancer Aid has been publishing the Blue Guidebooks. These are primarily directed towards people who have cancer and their relatives. They provide general information about different types of cancer, risk factors, follow-up exams, entitlement to benefits and much more. The brochure “Nutrition in Cancer,” first published in 1993, is regularly updated and distributed free of charge, as are all Blue Advisors.

Deutsche Krebshilfe, 1993 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

A rebuttal

In 1982, Christiane Lenker (pseudonym) fell ill with breast cancer. As a patient, she read Fritz Zorn’s book, Mars. She found Zorn’s theory that his own cancer was brought on by his callous, bourgeois upbringing depressing. In her rebuttal, she suggests viewing cancer as an “opportunity” to overcome the fears and self-doubt triggered by the disease.

Christiane Lenker, 1988 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Memoirs

Barbara Seuffert’s book is one of many memoirs, which tend to be written by women. In addition, since the 1980s, more and more guides to cancer have been published by psychologists.

Barbara Seuffert, 2001 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Guidebook

The cancer guides written by the American therapist Lawrence LeShan are still popular in Germany today. LeShan argues that ‘right’ attitudes and feelings can help to positively influence the course of cancer and to protect oneself from cancer.

Lawrence LeShan, 1982 | Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Operating on cancer

Early on, surgeons attempted to cure cancer with surgery. With the new understanding that most cancers develop locally, surgery gained scientific legitimacy as a treatment option. Thanks to the introduction (1846) and development of anesthesia, surgeons were now able to remove deeper tumours. Additionally, hygienic standards in operating rooms improved drastically in the second half of the 19th century. The mortality rate of patients undergoing surgery declined making the risks of surgical cancer treatments appear increasingly acceptable.

Patients-Stories

Cervical cancersurgery

The case historyof Auguste B.

On May 26th, 1907, Auguste B. went to the Charité women’s clinic.

Although, at 59 years old, she hadn’t had a period for eleven years, she had been bleeding throughout January and February.

Shortly thereafter, she noticed aching in her lower left abdomen. In the beginning of May, the pain became increasingly severe and she started bleeding again.

The symptoms she described concerned the gynecologist. A thorough examination confirmed the doctor’s suspicion: Auguste B. was suffering from advanced cervical cancer.

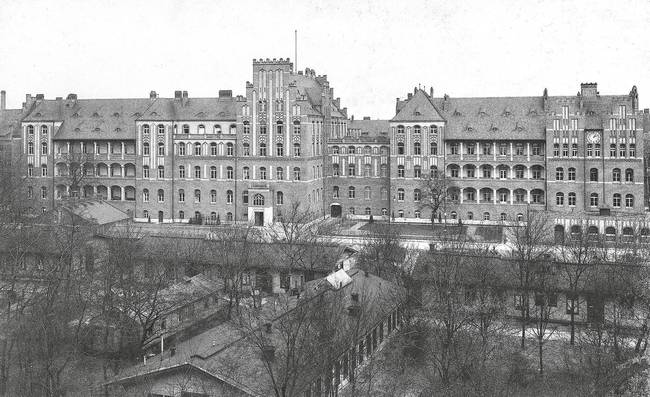

Fig. 1/4 University Women’s Clinic in Berlin, before 1906

The tumor was already large.

It had grown into Auguste B.’s bladder and vagina, which meant there was no longer any prospect of a cure.

Nevertheless, the doctors decided to operate, knowing that the operation was highly risky.

Later, a doctor who was an intern at the time of the surgery, justified the decision in a scientific article by stating that surgeons must practice surgical techniques in order to perfect them for the benefit of future patients.

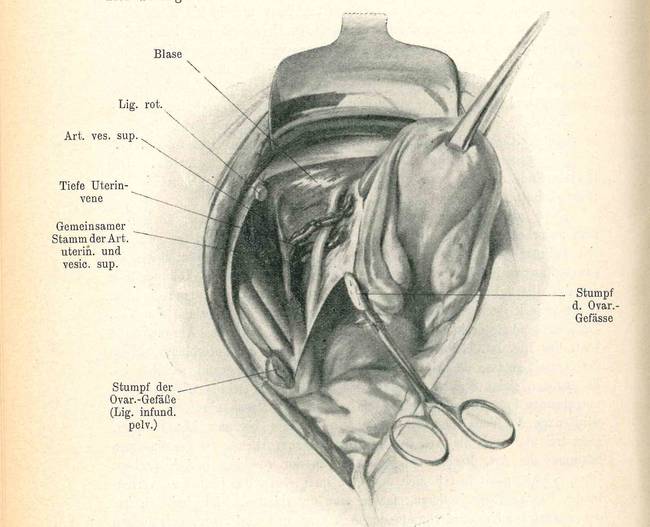

Fig. 2/4 Medical drawing: Pelvic exenteration

The operation took an hour and a half to complete.

They removed Auguste B.’s uterus and a pair of her glands. When they tried to detach the tumor from the posterior pelvic wall, it disintegrated.

The day after her operation she was writhing in pain, could hardly move and was constantly vomiting. She was also running a high fever.

Doctors and nurses immediately recognized that the patient was suffering from inflammation in her abdominal cavity. At the time, this was a frequent and feared complication of this operation.

Fig. 3/4 Aseptic operating room, ca. 1910

It was an infection that caused Auguste B.’s death, not cancer.

It’s true that surgeons washed their hands before every operation and used sterile surgical instruments; patients’ skin was thoroughly cleaned and operations were no longer performed in crowded lecture halls, but in separate, aseptic areas.

Microbiological research had impressively proven the essentiality of proper sanitation in operating rooms.

Nevertheless, in 1907, when the uterus was removed, one fifth of patients still died due to operation-related infections or other complications.

Fig. 4/4 Surgical operation in a lecture hall, before 1905

Treatment ofbowel cancer

The case history of Wilhelm K.

November 1913: Wilhelm K. went to a general practitioner in a private practice.

He had been suffering from severe abdominal pain for several weeks and was constantly exhausted.

The doctor performed a thorough physical exam and then recommended that the patient go to a clinic.

To avoid causing Wilhelm. K. to worry, the doctor chose not to tell him that he had symptoms of cancer.

Fig. 1/7 Charité, II. Med. Clinic, 1909/10

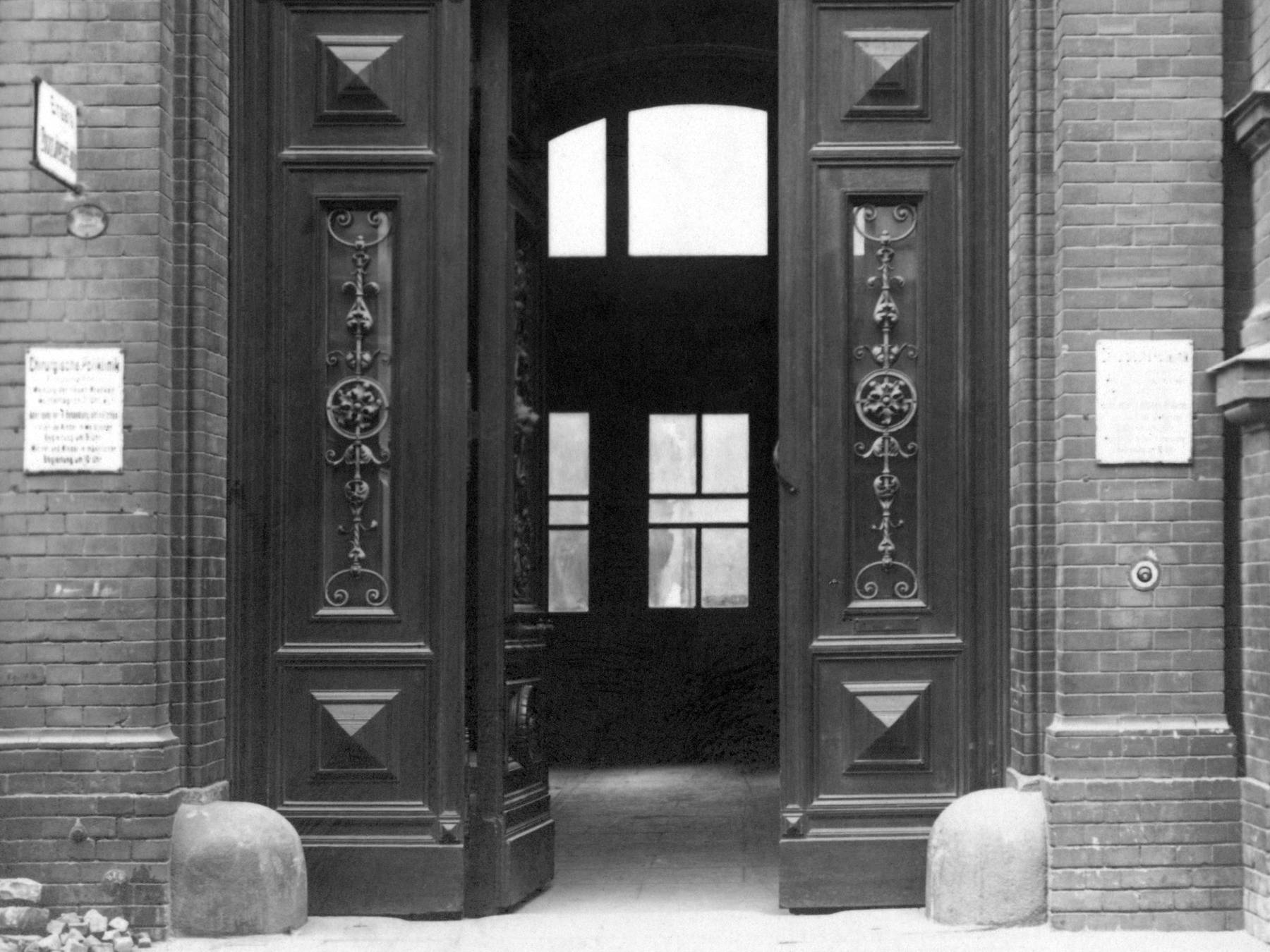

Around 9:00 am on December 3rd, 1913, the patient arrived at the surgical wing of the Charité.

The large building, its bare corridors with oppressive signage, and the smell of disinfectant intimidated the 59-year-old man.

He was feeling agitated as fear welled up inside him.

When a covered patient was carried past him on a stretcher, Wilhelm K. wanted to leave the hospital immediately.

Fig. 2/7 Charité, Hospital admission, 1910

At the hospital, Wilhelm K. was comprehensively examined.

X-ray imaging confirmed the suspicion: Wilhelm K. had bowel cancer.

He was taken to the surgical ward where seven hospital beds were already occupied: three patients with broken bones, one case of appendicitis, a gunshot wound to the abdomen, and two amputations.

Doctors tried not to put new cancer patients and post-operative cancer patients in the same room to avoid exposing them to surgery stories. Frightened patients needed stronger anesthesia, which increased the risk of surgery.

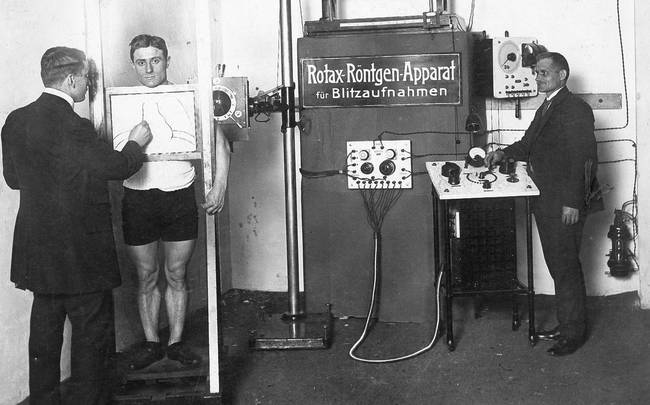

Fig. 3/7 X-ray examination in Berlin, 1912

Wilhelm K. didn’t find out what he was suffering from in the hospital either.

The doctors only disclosed which organ they would operate on.

He was also left in the dark about the severity of the operation. Doctors themselves couldn’t always correctly predict this before the operation. At that time, x-ray images were often ambiguous.

The surgeon removed suspicious tissue from the anesthetized patient, which was subsequently examined at the Institute of Pathology. The diagnosis was confirmed, and the doctors decided to perform radical surgery.

Fig. 4/7 Charité, Aseptic operating room, ca. 1910

Wilhelm K. woke up from anesthesia in a changed body.

He now had an artificial intestinal opening, or stoma, on his abdomen where excretions could escape.

No one had prepared him for this upsetting surprise and he wondered how the operation would change his life.

The attending doctors had deliberately left the patient out of their decision-making process. The knowledge, they thought, would cause unnecessary fear in their patients. Instead, they would be faced with a fait accompli and forced to resign themselves to reality.

Fig. 5/7 Charité, Hospital hall, 1909

Discharged “cured”?

After being discharged from the hospital, Wilhelm K. had to learn how to live with a stoma.

The fecal incontinence could be controlled, to some extent, by a strict diet and daily enemas. The gas, however, was uncontrollable, so he hardly ever went out in public.

He had regular check-ups because the doctors anticipated a relapse or new metastasis, but they didn’t tell Wilhelm K. about that either. Instead, they told him that after operations, benign ulcers could sometimes form and should be treated quickly.

Fig. 6/7 Entrance hall, Charité, II. Med. clinic, ca. 1910

Wilhelm K. is a fictitious patient.

However, many real cancer patients had similar experiences at the beginning of the 20th century.

Doctors usually left them in the dark about their disease as well as the surgical procedures and their outcomes.

In an effort to prevent cancer patients from dying at all costs, they made full use of the new medical possibilities. The patients’ quality of life thereafter often seemed to be secondary to them.

Fig. 7/7 Charité, II. Med. clinic: directors room, ca. 1910

Treatment of aprostate carcinoma

The case historyof Alfred P.

In 1987, Gertrud P. urged her husband to see a urologist.

Alfred P. had been having difficulties urinating for some time, but he brushed it off.

It was just because he was getting older, he said, and he didn't need to go to the doctor for every little thing.

When his symptoms became more severe, Alfred P. finally went to see a specialist, who referred him to a urology clinic. There, doctors found a malignant tumor in the prostate gland (prostate cancer), the most common type of cancer in men.

Fig. 1/5 Elderly couple, 1981

Alfred P. was informed of the diagnosis.

The urologist informed Alfred P. about the disease and gave him detailed explanations of the treatment options and their side effects.

An analysis of the tumor’s development showed that it was the only tumor and it was growing, but there was no evidence of lymph node involvement or metastasis. The patient’s overall health was good; his average life expectancy was still about 10 years.

Based on these characteristics, the urologist advised a complete removal of the prostate gland. Alfred P. asked for time to think it over.

Fig. 2/5 Medical drawing: Removal of prostate, 1991

A friend advised him to see a specialist in alternative cancer medicine.

Alfred P. went to a well-known surgeon who firmly rejected the “cancer scare” and radical treatments that he believed were associated with it.

He held that malignant cancer was a “disease of the soul” and a “biological punishment from God” for decades of sinning against oneself.

The surgeon invited Alfred P. and his relatives to a meeting where he advised the patient to undergo detoxification treatments, nude outdoor bathing therapy and to focus more on life enjoyment.

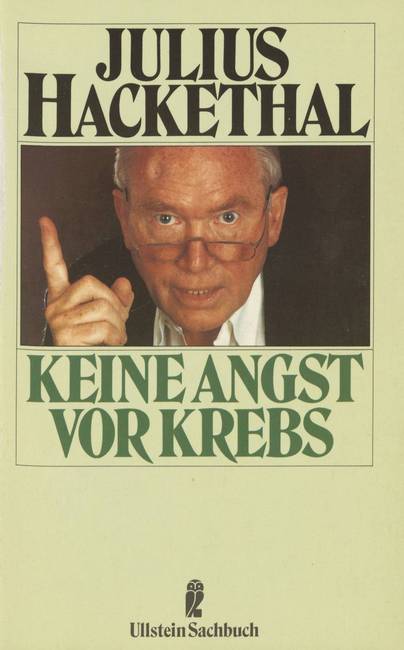

Fig. 3/5 J. Hackethal advocated alternative cancer medicine.

Ultimately, Alfred P. decided to have a radical prostatectomy.

An experienced surgeon removed the prostate, the seminal vesicle and the vas deferens.

After the operation, Alfred P. dealt with incontinence and could no longer get an erection. The post-operative effects caused him mental anguish.

But the consequences of the operation were only temporary: after three months he was able to get erections again, and a year and a half later he could control his urination.

Fig. 4/5 Surgical team, 1996

Alfred P.’s recovery was facilitated by his stay in a rehabilitation clinic.

There, he received both medical and psychological care. He learned how to deal with his body’s new limitations caused by the operation and he met patients who he could talk to for support. That gave him courage.

Such after-care clinics were innovations set up in the post-war period, first in the GDR and later in the FRG.

Understanding that transitioning from the hospital to everyday life was difficult and could jeopardize the success of expensive cancer therapies motivated the establishment of these clinics.

Fig. 5/5 Rehabilitation center, 1993

Credits

The case history of Auguste B.

Images

Fig. 1/4 University Women’s Clinic, before 1906.

Charité, Thiele, Bild-Nr. 001371

Fig. 2/4 Med. Drawing, from: E. Bumm, Zur Technik der Beckenausräumung beim Uteruskarzinom, in: Charité-Annalen, hg. v. der Direktion des Königl. Charité-Krankenhauses zu Berlin, 1907, S. 429-438, hier: S. 434.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Berlin

Fig. 3/4 Charité, Aseptic operating room, ca. 1910.

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 001460

Fig. 4/4 Preparing for surgery in the lecture hall of the Surgical Clinic of the Charité, before 1905.

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 001455

The case history of Wilhelm K.

Images

Fig. 1/7 Charité, II. Medical Clinic, 1909/10.

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 001504

Fig. 2/7 Charité, Hospital admission, 1910.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Berlin, Bild-Nr. 001506

Fig. 3/7 X-ray examination in Berlin, 1912.

Scherl/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo, REF 108677

Fig. 4/7 Charité, Aseptic operating room, ca. 1910.

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 001488

Fig. 5/7 Charité, Hospital room, 1909

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 000895

Fig. 6/7 Entrance hall of the II Med. clinic, ca. 1910.

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 001492

Fig. 7/7 Charité, II Med. clinic: directors room, ca. 1910.

Charité, Lichte, Bild-Nr. 000887

The case history of Alfred P.

Images

Fig. 1/5 Elderly couple, 1981.

Werner Otto/Alamy Stock Foto, Bild-ID BA3RAW

Fig. 2/5 Med. Drawing: Removal of the prostate, from: H. Frohmüller und M. Wirth, Die radikale Prostatektomie, in: R. Ackermann, J. E. Altwein, P. Faul (Hg.), Aktuelle Therapie des Prostatakarzinoms, Berlin u. a.: Springer-Verlag 1991, S. 100-121, hier: S. 110.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Fig. 3/5 Julius Hackethal, Keine Angst vor Krebs, Frankfurt/M. und Berlin: Ullstein Verlag 1987.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Fig. 4/5 Surgical team at the Nuremberg North Hospital, 1996.

Karin Rummel/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo, REF 80120

Fig. 5/5 Le Noirmont, Centre Jurassien de réadaptation cardiovasculaire, (Rehab Center, Jura, Switzerland), 1993.

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Zsolt, Somorjai / Com_FC19-2340-003 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Radiating cancer

Radiation therapies have complemented surgical treatments since the 1910s. Just a few years prior, X-rays and radium rays were discovered. Not yet fully understanding the effects of the high-energy rays, physicians immediately tested their therapeutic benefits. They discovered that malignant tumors softened and shrank when irradiated, but what dose of radiation was required to destroy a tumor? How much radiation could the patients tolerate? How could the tumor be targeted? And how could healthy tissue be protected? To this day, these questions preoccupy radiation oncology, which established itself as an independent discipline in the postwar period.

Patients-Stories

Treatment of penile carcinoma

The case history of Walter H.

“Radiation enthusiasm”

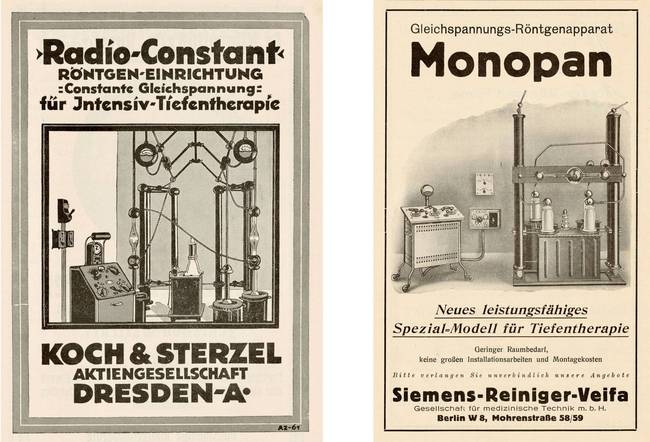

Early in the 20th century, physicians, physicists, electrical technicians and engineers across the western world focused their efforts on radiation therapy.

Procedures and medical machines were refined to penetrate the body more precisely, preserving as much healthy tissue as possible.

By the 1920s, radiation was already considered a central element of cancer therapy. Hospitals built their own radiation departments and radiology became well-established as an independent discipline.

Fig. 1/6 Advertisements for new irradiation devices, 1921

Were the innovative treatment methods adopted prematurely?

In the case of 52-year-old Walter H., this may have been true. In 1921, the advertisement copywriter felt an itching sensation on his genitals and noticed a nodule under his foreskin. When his symptoms didn’t go away on their own, he went to see a dermatologist.

After several unsuccessful attempts at treatment, he was sent to the hospital for further testing.

There, the doctors diagnosed Walter H. with a rare type of cancer: penile carcinoma.

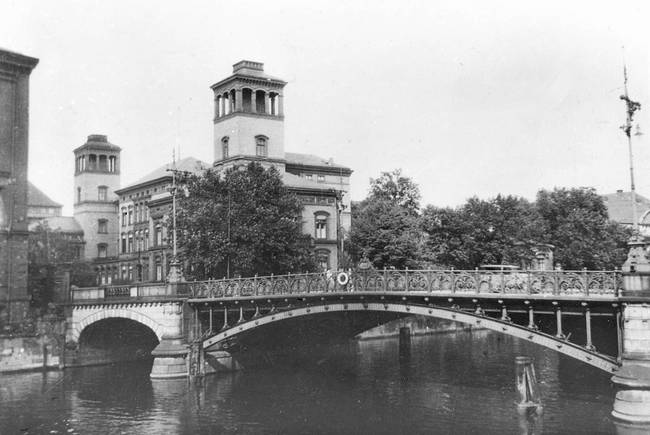

Fig. 2/6 Surgical University Hospital of the Charité

The surgeons were very hesitant to operate on Walter H.

Penile amputation would be severely traumatic.

So, after consulting with radiologists and likely with Walter H. himself, the doctors felt that X-ray radiation was the best way forward.

They were encouraged by the work of their colleagues, who had successfully treated similar skin cancers using this method.

Fig. 3/6 Radiologist in the 1920s

Due to the expensive radioactive substances, the therapy was costly.

In 1921, the statutory health insurers paid 2,000 Reichsmarks for six rounds of irradiation.

People who did not have health insurance, like many higher-up officials and the self-employed, often could not afford the therapy.

Being that he self-employed, Walter H. was not covered by a statutory health insurance fund. However, he was voluntarily insured by a private fund, which covered the costs of his radiation therapy.

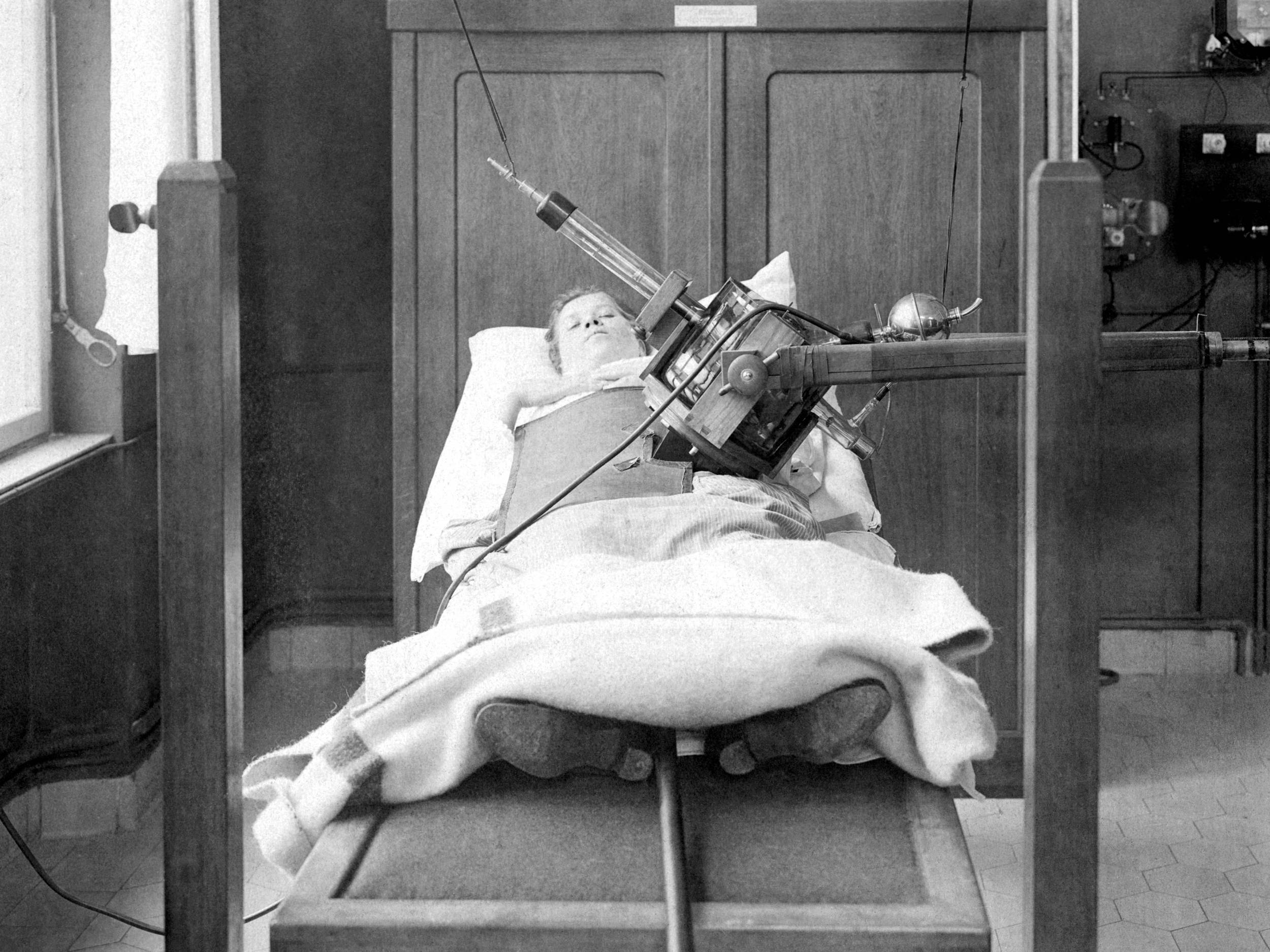

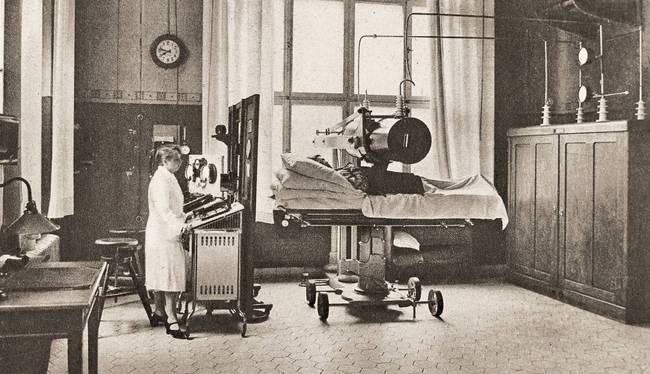

Fig. 4/6 Irradiation technique “Wintz-Kanone”, ca. 1925

A high-tech radiation device was used to target the tumor.

At first, the therapy considerably reduced the tumor’s size, but after two weeks the shrinkage plateaued.

As a side effect, Walter H. developed an “X-ray hangover.” This left him exhausted, vomiting frequently, and suffering from both severe diarrhea and the constant urge to urinate. Urinating became more and more painful. Additionally, the tumor began decaying as it accumulated bacteria, producing a foul odor.

Finally, his doctors decided it was time to operate. Not long after his operation, the father of four died in the hospital.

Fig. 5/6 X-ray irradiation, ca. 1931

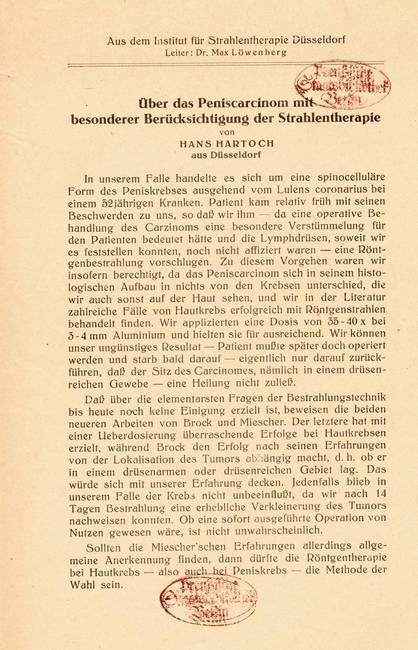

Looking back, the doctors recognized that they had made the wrong decision.

The attending radiologist later wrote in an article that an immediate operation followed by a stronger dose of radiation would likely have been more successful.

Unfortunately, he explained, very little information about radiation dosages was available to them at the time.

Such regretful expressions of self-criticism are rarely found in medical publications from the 1920s. Failed treatments were typically framed as an opportunity for learning and a prerequisite for the optimization of cancer therapies.

Fig. 6/6 Hans Hartoch, Über das Peniscarcinom, 1923

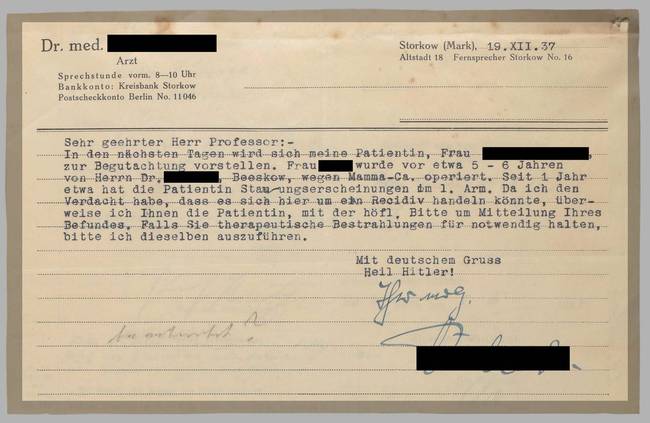

Breast cancer relapse therapy

The case history of Minna N.

In October of 1932, Minna N. underwent an operation in the Beeskow hospital.

Doctors had discovered a malignant tumor about the size of a walnut in her left breast.

To save Minna N., who was 46 years old, they decided to perform a radical operation, as was the standard procedure at the time.

She had a mastectomy, which involved the removal of her mammary gland, skin and nipple.

Fig. 1/5 Picture postcard from Beeskow, ca. 1900

Four years later, her cancer relapsed.

In 1936, by which time Germany was under National Socialist rule, Minna N. went to see her family doctor.

There had been swelling in her left arm for a while. When massages and heat therapy didn’t relieve her symptoms, her worried doctor referred her to the Surgical University Clinic in Berlin.

There, his suspicions were confirmed: A new tumor had formed in Minna N.’s chest wall and there was evidence of metastasis in her thorax (chest cavity). The cancer had progressed from local to systemic, which meant that it was no longer curable.

Fig. 2/5 Referral to the Charité in Berlin, 1937

There is a possibility that Minna N. was informed of her diagnosis.

The philosophy that patients should be informed “truthfully” and “factually” of their terminal illness gained popularity under National Socialism.

People now believed more often that “gently lying” in order to calm fears of death and dying should no longer be practiced by doctors.

They considered dying to be a German’s “final test of strength”. This shouldn’t be taken away from them through the deliberate omission of information. Following this logic, some even considered it wrong to give patients painkillers.

Fig. 3/5 Psychiatrist F. Künkel expressed this view at the meeting.

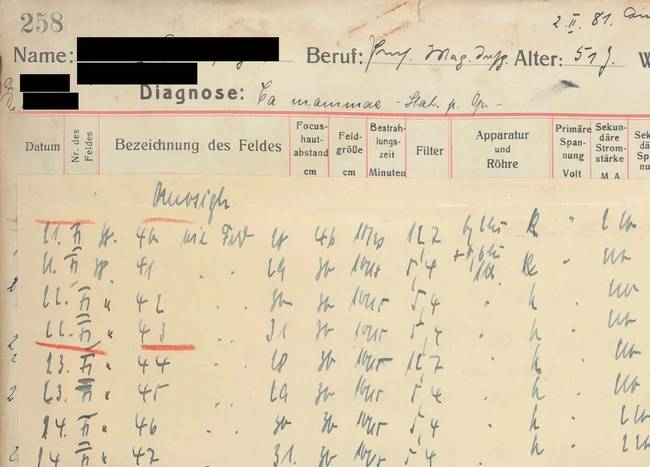

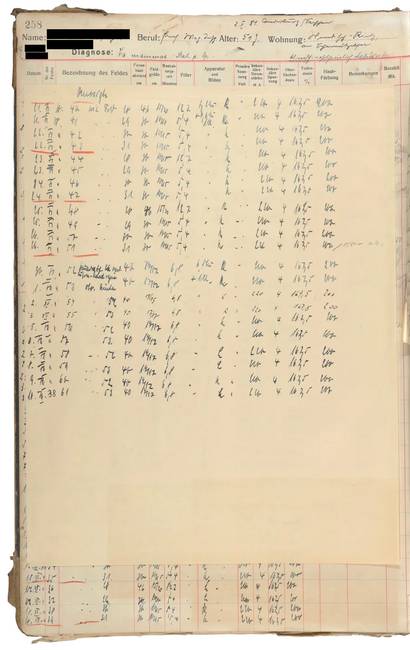

Radiation therapy was believed to slow the progression cancer.

So, Minna N. went through radiotherapy at the X-Ray and Radium Institute in the university’s surgical clinic.

In her patient file, the doctors recorded minimal side effects: “no nausea, no vomiting, undisturbed appetite and sleep.” Reddening of the skin in the target area was the only negative aftereffect.

A note taken some time later, however, reveals that Minna N. didn’t come in for a follow-up appointment in June of 1938, “because she was supposedly away on a rehabilitative trip.”

Fig. 4/5 Irradiation protocol from patient file, 1937

Minna N. died on March 2nd, 1940.

How the patient fared between the missed checkup in June 1938 and her death cannot be inferred from her medical file.

Overall, the quality of care available to patients of terminal cancer deteriorated dramatically under National Socialism.

One reason for this development was the conviction that only healthy “Volksgenossen” were valuable. What’s more, people who were important to the war effort were given priority for medical care from 1939 on.

Fig. 5/5 Ceremony at the Berlin University Women’s Hospital, 1941

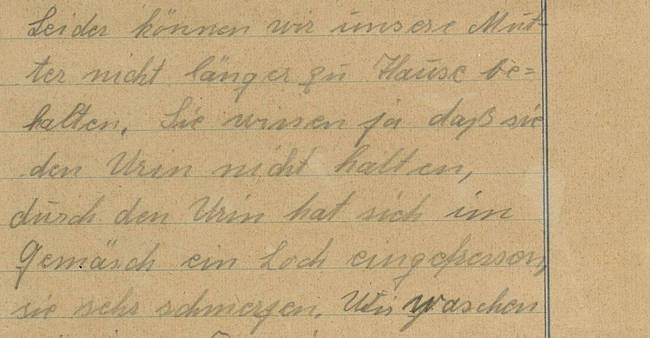

A relative described his experience in the critical care ward of the Charité in 1940:

“Even the entrance must horrify the patient, through which he is brought to this dungeon. (…)

The toilet in the men’s ward can only be reached through the bathroom, which is shared between all sexes. In front of this bathroom is the only utility and storage room, where those who have fallen victim to their illness must be housed until they are taken away. (…)

The most modest recreation room is missing, (…) as is any attempt to (…) offer the sick (…) some comfort and courtesy.”

Cervical cancer

The case history of Hilde W.

A cry for help was heard in the Czerny Hospital.

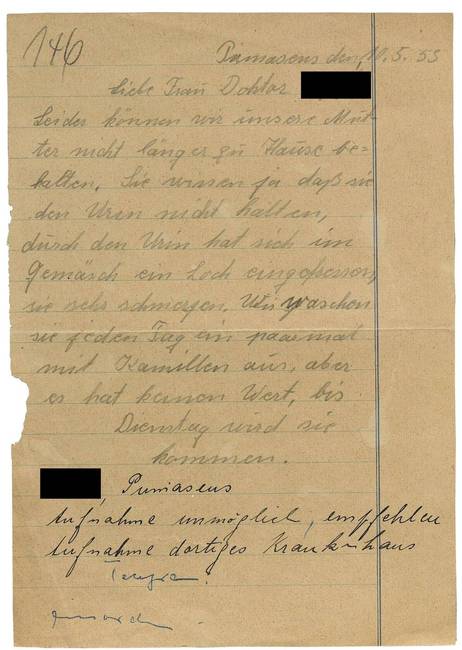

In May of 1953, the renowned Heidelberg Hospital for Radiotherapy received a letter from the daughter of cancer patient Hilde W., who wrote that family could no longer care for her mother at home.

She asked for permission to bring her seriously ill mother back to the clinic where she had been treated previously.

Like most families who lived in cramped quarters and could not afford a nurse, Hilde W.’s family was overwhelmed by the care she required.

Fig. 1/6 Daughter’s letter to the hospital, May 1953

Just a year earlier, there were no indications that Hilde W. was ill.

In February 1952, at 41 years old, she discovered that she was pregnant; she was anything but happy about it.

Her husband had been unemployed for months and of her ten children, five were still of school age.

Hilde W. considered terminating the pregnancy, but it would have been a crime. Women who decided to have an abortion could face as many as five years in prison.

Fig. 2/6 Social housing construction, FRG, 1950s

Her pregnancy continued without complications.

Hilde W. paid no attention to her light, ongoing bleeding.

On November 22nd, 1952 she went into labor and began bleeding more heavily. She went directly to the municipal hospital in Pirmasens, Palatinate thinking that she was about to give birth.

Her labor dragged on. Finally, the doctors decided to perform a C-section.

Fig. 3/6 Delivery room, operating room, ca. 1960

During the operation, the surgeon realized why the birth had stalled.

Hilde W. had cervical cancer. The cancer had already spread to the neighboring organs and was hindering the birth.

The doctors delivered the child, a viable girl, and removed part of the tumor. That was all they could do for the patient.

Hilde W. was referred to the Czerny Hospital for Radiation Treatment for follow-up radiation, although she wasn’t aware that she had cancer. At that time in the Federal Republic of Germany, it was normal to leave patients uninformed of their cancer diagnosis.

Fig. 4/6 Samaritan House in Czerny Hospital, built in 1905

The tumor was irradiated using X-rays.

In addition, Hilde W. had radioactive cobalt inserted into her vagina and bladder.

In the 1920s, it was already common practice to combine internal and external radiation. The goal was to effectively destroy the cancer cells while sparing as much healthy tissue as possible.

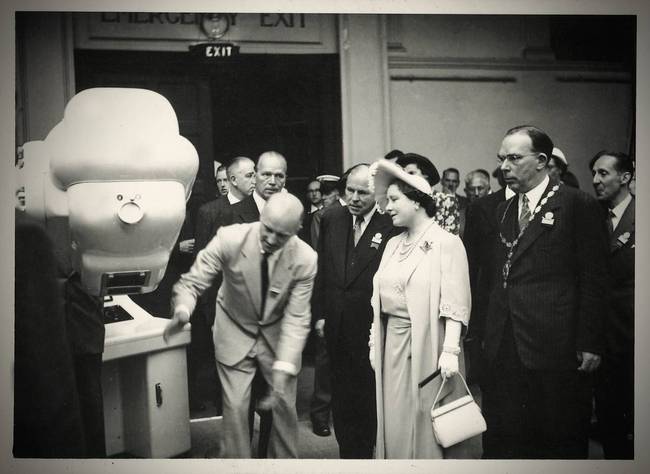

Just a few years later, doctors attempted to achieve the same effect by using new radiation devices: the betatron, the cyclotron or gammatron.

Fig. 5/6 Betatron presentation, X-ray Congress, London, 1950

Hilde W. was not readmitted to the Heidelberg hospital.

Instead, her family took her to the municipal hospital in Pirmasens, where she died at 42 years old.

Unlike the GDR, in the 1950s the Federal Republic of Germany didn’t provide any nursing homes to care for the seriously ill and dying.

In the FRG, people were meant to be cared for at home by (female) relatives if they were sick or nearing the end of their life. This expectation was reinforced early in the 1960s through legislation and state support payments.

Fig. 6/6 Note to Czerny Hospital, May 1958

Credits

The case history of Walter H.

Images

Fig. 1/6 Two advertisements for irradiation devises, from: Strahlentherapie. Mitteilungen aus dem Gebiete der Behandlung mit Röntgenstrahlen, Licht und radioaktiven Substanzen, zugleich Zentralorgan für Krebs- und Lupusbehandlung, Bd. XXI, 1921, Berlin/Wien: Verlag Urban & Schwarzenberg.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Fig. 2/6 Former surgical university hospital of the Charité in Ziegelstraße, undated.

Charité, Fleischbein-Brinkschulte, Bild-Nr. 002968

Fig. 3/6 Guido Holzknecht (1872-1931), Austrian physician, pioneer of radiology, Vienna University Hospital, 1920s.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Bild-Nr. 020054

Fig. 4/6 Irradiation “Wintz gun” and first devices of radiation protection, ca. 1925.

Nachkommen des Verlagsinhabers Krüger/Universitätsarchiv Erlangen, Sig. E5,3 Nr. 142

Fig. 5/6 X-rays, photograph from the exhibition „Kampf dem Krebs“ (Fighting Cancer), ca. 1931.

Deutsches Hygiene-Museum Dresden, Inv.-Nr. DHMD 2001/247.135

Fig. 6/6 Hans Hartoch, Über das Peniscarcinom mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Strahlentherapie, Köln: Kerschgens 1923.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

The case history of Minna N.

Images

Fig. 1/5 1/5 Picture postcard from Beeskow (Brandenburg), ca. 1900.

Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Fig. 2/5 Referral to the Berlin Charité, document from a patient file, Geschwulstklinik (Ulcer Clinic), 1937.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Berlin

Fig. 3/5 Invitation to the meeting of the working group between physicians and clergy on 2.9.1937.

Landesarchiv Berlin, A Rep. 003-04-03, Nr. 55

Fig. 4/5 Irradiation protocol from a patient record at the Geschwulstklinik (Ulcer Clinic), 1937.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Berlin

Fig. 5/5 Ceremonial act at the Berlin University Women’s Hospital on the occasion of the 70th birthday of the gynecologist Walter Stoeckel (1871-1961), 1941.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin

The case history of Hilde W.

Images

Fig. 1/6 Letter to Czerny Hospital for Radiation Therapy, dated 10.5.1953.

Universitätsarchiv Heidelberg, Acc. 14/02, Nr. 17342

Fig. 2/6 Münster-City, Blumenstraße reconstruction community, managed by GAGFAH - Gemeinnützige Aktiengesellschaft für Angestellten-Heimstätten, ca. 1955.

Sammlung LVA Westfalen: Wohnungsnot und Wohnbauförderung in den 1920er-1950er Jahre, Archiv-Nr. 03_3865

Fig. 3/6 University Women’s Hospital Berlin, delivery room - operating room with examination couch, 1960.

Charité, Thiele, Bild-Nr. 001884

Fig. 4/6 “Samariterhaus” (Samaritan House) in Czerny Hospital, built in 1905/06.

Universitätsarchiv Heidelberg / Bildarchiv Pos I 03761

Fig. 5/6 Queen Elizabeth (Queen Mum) looks at the betatron at the International Congress of Radiology in London, 1950.

Siemens Healthineers Historical Institute, A 54_13

Fig. 6/6 Notice from a registrar of the patient’s death to the Czerny Hospital for Radiation Treatment, dated 5.9.1958.

Universitätsarchiv Heidelberg, Acc. 14/02, Nr. 17342

Chemotherapy

As early as 1900, physicians began searching for drugs that could fight cancer. Inspired by the spectacular successes of bacteriology, they experimented with various therapeutic substances to combat cancer cells. It was not until observing the effects of chemical weapons used during the First and Second World Wars that their attention turned to substances that could attack and inhibit the growth of human cells rather than pathogens. After 1945, large-scale programs in the USA continued research in this direction and various groups of substances were successfully tested for their anti-cancer effects.

Chemotherapeutic agents were initially investigated in relation to the treatment of leukemia and lymphoma. In the 1950s, there was no prospect of a cure for leukemia, and it was known that neither type of cancer could be treated locally. Therefore, high hopes were pinned on the new systemic cancer drugs. In the 1960s and 70s these drugs were only able to delay death for cancer patients. However, in the following decades, the new drugs significantly improved their chances of being cured. For the patients, the novel treatment represented hope for a cure, but also considerable pain with most people suffering a dramatic physical deterioration at the onset of treatment.

Patients-Stories

Leukemia becomes treatable

The medical history of four-year-old Regina

Regina was a carefree child.

She was born in 1966 and later developed into a bright, lively girl. She enjoyed kindergarten and almost never got sick.

When Regina was just shy of five years old, she began to complain more and more of fatigue and joint pain. She lost her desire to play as well as her appetite.

Her parents brought her to the family doctor, who immediately sent her for tests at the local children’s clinic.

Fig. 1/6 Mother with children, 1963

The doctors at the clinic discovered that Regina was suffering from blood cancer.

She had a form of acute leukemia, a cancer affecting the development of blood cells within bone marrow.

Her diagnosis was explained to her parents, but it was difficult for them to understand and they didn’t want to ask too many questions.

They had never heard of this new cancer treatment, which was the first one that could delay the progression of the disease and, in rare cases, might even be a cure.

Fig. 2/6 Children’s hospital, 1969

Regina had to stay in the hospital for six weeks.

She went through aggressive chemotherapy, requiring a combination of drugs.

The side effects were serious: the four-year-old vomited constantly, suffered severe diarrhea, did not want to eat, and contracted a life-threatening infection.

During this time, her parents didn’t visit her. The doctor had advised against visits so as not to upset the child and her parents followed his advice.

Fig. 3/6 Pediatric clinic, hospital room, undated

For the four-year-old, it was her first time being away from her parents.

She was homesick and became increasingly quiet. She befriended a boy who was also suffering from leukemia, but when he died, she didn’t want to play with any other children in the clinic.

When her parents picked her up from the hospital after the successful treatment, they hardly recognized her:

Her body and face were bloated, and her hair had fallen out. The girl, who used to be so cheerful, had become solemn. She couldn’t be left alone, and she would scream in her sleep.

Fig. 4/6 Children’s hospital, day room, undated

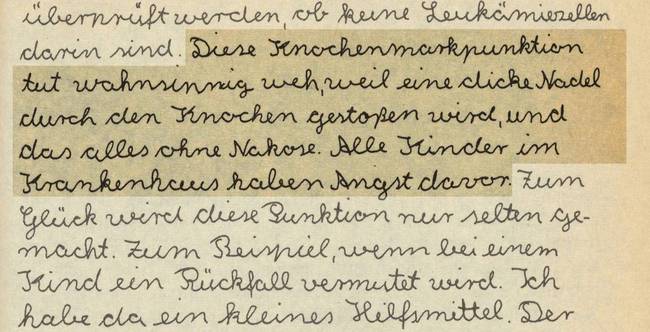

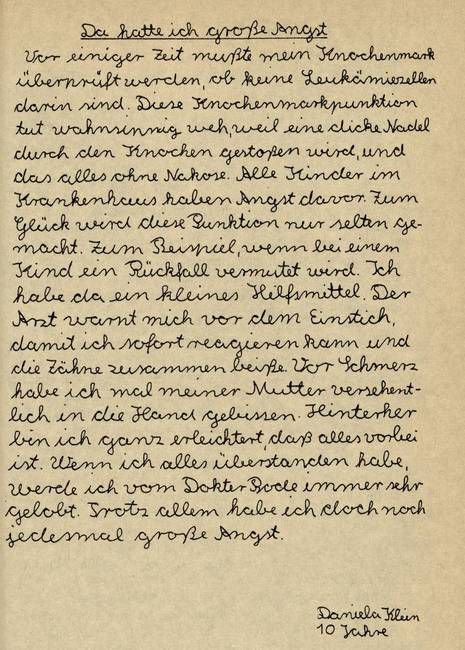

After her hospital stay, the outpatient appointments began.

For two years, Regina’s mother took her to the hospital every six weeks for check-ups.

At every appointment, they performed a bone marrow puncture to check for signs of a relapse. To ease the pain of the puncture, Regina was meant to inhale an anesthetic.

Each time, she resisted the face mask with all her might because the anesthetic made her feel like she was falling into a deep, dark lake.

Fig. 5/6 A 10-year-old describes follow-up examination

The anesthesiologist criticized Regina’s mother for her child’s behavior:

She could sense her mother’s angst and insecurity, causing her fearful protests.

According to the doctor, it was up to the parents to prepare the children well, then they would be ready to endure the procedure.

Neither the child nor the parents were offered psychological support, although medical literature had already noted its importance to the treatment’s success.

Fig. 6/6 Entrance of a children’s hospital

Regina’s leukemia didn’t return.

She was one of the 1-2 % of children who were cured of their acute leukemia in the early 1970s with the help of the new chemotherapeutic drugs.

For 98-99% of children, however, the new drugs could only lessen their symptoms and delay their death.

In the decades that followed, more and more children were cured. Nonetheless, “cured” did not always mean healthy. Many survivors suffered long-term side effects of their treatment into adulthood, such as metabolic disorders, organ damage, infertility or anxiety.

A drug trial in the GDR

The medical history of Karin S.

Karin S. had run out of patience.

She had been enduring her illness for so long. In September of 1986, doctors at the East Berlin Women’s Clinic of the Charité Hospital gave her the news that they found a malignant tumor (mammary carcinoma) in her right breast.

She had a complete mastectomy. After her wounds healed, Karin S. received radiation treatment.

In July of 1987, the doctors advised her to undergo chemotherapy after discovering metastasis in her liver.

Fig. 1/5 University Women’s Clinic East Berlin, ca. 1980

Once a week, Karin S. had to be “put on a drip”.

Each time, she watched as the cytostatic drug flowed from the syringe into the veins in her arm. The drug is supposed to kill the rapidly dividing cells.

Although the “poison” exhausted her, she couldn’t sleep. She lost her ability to concentrate and could hardly read. After the infusions, she vomited repeatedly.

She felt like the drug also extinguished her courage, her vitality, and her happiness.

Fig. 2/5 Chemotherapy (ZIK, East Berlin)

The early morning hours were the worst.

She was awoken from her dreams and fear swelled inside her. No one, she was sure, could ever understand the horror if they hadn’t experienced it themselves.

In front of her family, she maintained a peaceful façade, but she saw the way her husband would occasionally struggle to hold back tears.

She was disturbed by people who avoided her gaze or who prophesized that everything would be all right if only she believed it would be.

Fig. 3/5 Univ. Women’s Hospital, hospital corridor, ca. 1980

The medicine used to treat Karin S. came from the West.

A doctor had asked her if she would be willing to take part in a clinical drug trial.

The study aimed to test the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of a cytostatic drug from the Federal Republic that had not yet been approved for treatment.

The doctors informed her of the possible side effects and complications. Regardless, she agreed immediately, hoping that the new drug would be a breakthrough in her therapy. It wasn’t a cure, but it prolonged her life by several months.

Fig. 4/5 Univ. Women’s Hospital, consulting room, ca. 1985

Western Companies commissioned a series of drug studies within the GDR.

In the field of oncology, 44 studies were verifiably conducted between 1961 and 1990. The GDR’s centralized system was desirable to drug companies as it accelerated the implementation and evaluation of the studies.

The GDR government came into Western currency through the commissions, as it received all the study fees, not the involved patients and doctors.

Doctors were able to travel to conferences in the West, given western trial drugs free of charge and sometimes granted access to medical technology unavailable in the GDR.

Fig. 5/5 Central Institute for Cancer Research (ZIK)

Lung cancer treatment

The medical history of Axel T.

Axel T. anxiously waited in the corridor of the university hospital in June of 1990.

The 64-year-old was waiting for his appointment with the oncologist.

His fear tormented him and his stomach was in knots. He felt like a guilty man waiting to receive a sentence.

Axel T. told himself to stay calm. In a moment he would have to focus in order to understand everything correctly. He might also be asked to make an important decision.

Fig. 1/6 Corridor with waiting room

Prior to this conversation, he had gone through several diagnostic tests:

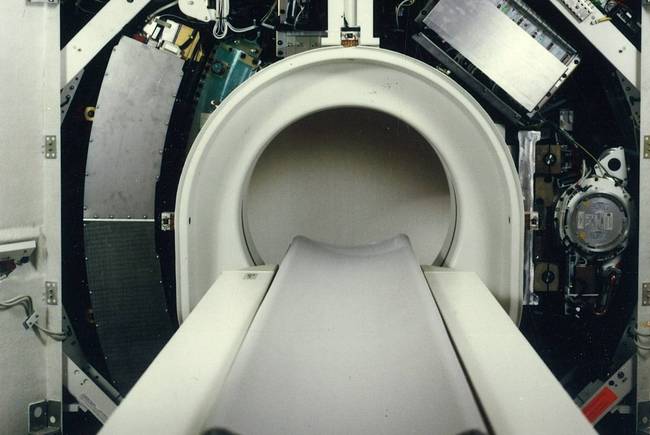

In addition to the conventional x-ray examination, doctors ordered a computer tomography - a new imaging procedure that made visible the spatial dimensions of the tumor.

Additionally, they performed a microscopic examination of the lung mucosa cells as well as a bronchoscopy (lung endoscopy), in which tissue samples were taken from the lung for further analysis.

Finally, they did a mediastinoscopy to determine the extent to which the lung cancer had spread.

Fig. 2/6 Computer tomograph: SOMATOM Plus, ca. 1988

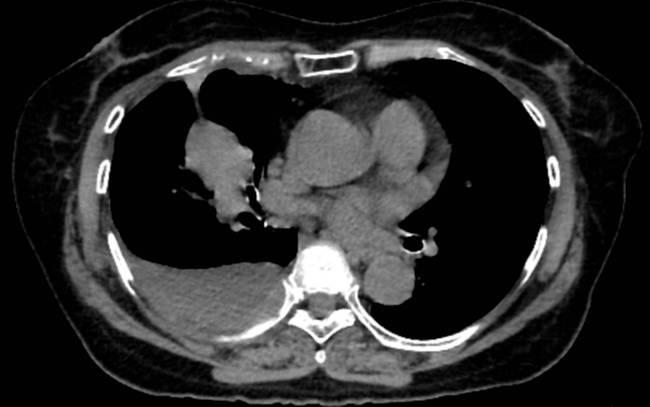

The oncologist diagnosed Axel T. with small cell lung cancer.

She explained that lung cancer has become one of the most common cancers found in industrialized countries.

According to current research, increasing cigarette consumption, environmental toxins, exposure to certain chemicals and minerals, as well as nutrition and genetic factors all contribute to the increased cases of lung cancer.

She told him matter-of-factly: The fast-growing cancer is characterized by a high rate of cell division, leaving little hope for a cure. However, there are therapies that can prolong one’s life.

Fig. 3/6 Lung cancer, CT scan of a 67-year-old man, undated

In light of his diagnosis, the doctors recommended a combination of treatments.

Axel T. was treated with four different anti-cancer drugs in three cycles.

Immediately after the first infusion, he was felt euphoric. He suffered almost no side effects. They would come later, as his hospital room neighbor warned, and he was right.

Diarrhea and stomach pain like he had never felt before, an inflamed oral mucosa, extreme fatigue, weakness and burning veins became commonplace for Axel T.

Fig. 4/6 Charité pharmacy, drug production, 1995

Between treatments and during breaks in his treatment he often felt relief from the side effects.

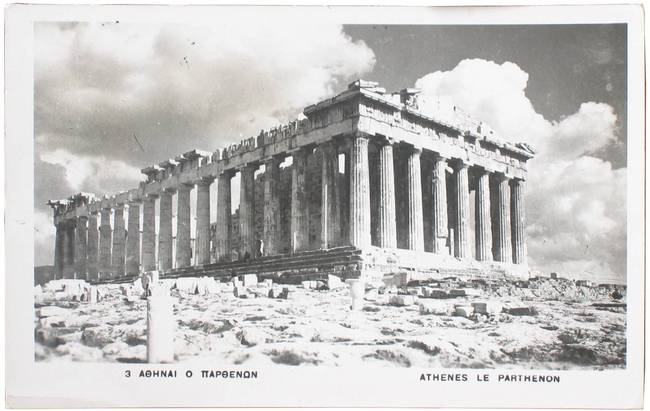

He didn’t want to wait any longer to fulfill his desires.

He travelled to Greece once again with his wife, he was happy when the children and grandchildren came to visit and tried not to miss any chances to see his childhood friends.

When the weather was nice, he went to the park to feel the sun and the breeze on his skin. There, he was amused by the sparrows and often ate his favorite kind of ice cream.

Fig. 5/6 Picture postcard, Acropolis, Temple of Pallas Athena

A psychologist from the clinic advised him to live in the moment.

The philosophy behind this was that seriously ill people must have hope. If their hope to be cured is futile, then their hope can instead be directed towards the little things, like going to the sea once again.

In the early 1990s, it was popular to think that hopeful thoughts could positively influence the immune system and, thus, the course of the disease.

Seriously ill people now increasingly found themselves called upon to have hope - an expectation that could sometimes also be a burden.

Fig. 6/6 Older man in a park

Credits

The medical history of four-year-old Regina

Images

Fig. 1/6 Mother with two children, Zurich-Oerlikon, corner Schaffhauserstrasse and Wallisellenstrasse, 1963.

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Comet Photo AG (Zürich) / Com_L12-0072-0008-0038 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Fig. 2/6 Children’s Hospital, Zurich, 1969.

Baugeschichtliches Archiv Zürich/Wolf-Bender’s Erben, Bildcode BAZ_118508

Fig. 3/6 Children’s Hospital Wedding, hospital room: nurses applying a leg bandage, child patient with head bandage, undated.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Bild-Nr. 009158

Fig. 4/6 Children’s Hospital Wedding, day room: nurse playing with several children, undated.

Charité, ZFA, Bild-Nr. 008948

Fig. 5/6 A ten-year-old describes a follow-up examination, from: Petra Kelly (Hg.), Viel Liebe gegen Schmerzen. Krebs bei Kindern, Reinbek: Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. 1986.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Fig. 6/6 Entrance of a children’s hospital, Zurich, built in 1939.

Baugeschichtliches Archiv Zürich/Wolf-Bender’s Erben, Bildcode BAZ_118569

The medical history of Karin S.

Images

Fig. 1/5 Entrance to the University Women’s Clinic in East Berlin, ca. 1980.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Berlin, Bild-Nr. 001428

Fig. 2/5 „Pharmaceutical industry tested drugs on patients in the GDR“, here: Drug tests in the ex-GDR, chemotherapy patient at the Central Institute for Cancer Research during infusion, 11.1.1991 (picture detail).

Berlin, Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur/Klaus Mehner, Inv.-Nr.: 91_0111_GES_MedTest_21

Fig. 3/5 University Women’s Clinic, corridor, ca. 1980.

Charité, Thiele, Bild-Nr. 001656

Fig. 4/5 Univ. Women’s Hospital, consultation room, ca. 1985.

Charité, Thiele, Bild-Nr. 001916Z

Fig. 5/5 „Pharmaceutical industry tested drugs on patients in the GDR“, Central Institute for Cancer Research/Academy of Sciences of the GDR, 11.1.1991.

Berlin, Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur/Klaus Mehner, Inv.-Nr.: 91_0111_GES_MedTest_23

The medical history of Axel T.

Images

Fig. 1/6 „In a corridor there is a waiting room“, 3.2.2016.

Marcel Derweduwen/Alamy Stock Photo, Bild ID FGJWHW

Fig. 2/6 Computer tomograph: SOMATOM Plus, ca. 1988.

Siemens Healthineers Historical Institute, Bild-Nr. 3122 abx

Fig. 3/6 Lung cancer, CT scan of a 67-year-old man, undated.

Rajaaisya / Science Photo Library / Alamy Stock Fotos, Bild ID 2GYNGY

Fig. 4/6 Pharmacy of the Charité, production of medicines, from: Antje Müller-Schubert, Susanne Rehm, Caroline Hake, Sara Harten, Charité. Fotografischer Rundgang durch ein Krankenhaus, be.bra Verlag: Berlin 1996.

Charité, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin, Berlin

Fig. 5/6 Picture postcard, Athènes, Le Parthenon, Postcard stamp 12.4.1951.

ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Fotograf: Unbekannt / Fel_052590-RE / Public Domain Mark

Fig. 6/6 Older man in a park, 2.4.2013.

Jürgen Ritterbach/Alamy Stock Foto, Bild-ID D5GDKE

Interviews

Being cured of cancer

Living with cancer

Dying of cancer

Even in the 21st century, medical care for people suffering from cancer continues to evolve. In addition to the classic therapies - surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy - there are now promising new forms of treatment, such as immunotherapy or molecularly targeted therapies. With these innovations, our understanding of cancer and the way we handle the disease have changed. The following twelve interviews reflect this change from different perspectives.

Being cured of cancer

While the diagnosis of cancer in 1900 was usually tantamount to a death sentence, today more than half of all cases of cancer are curable. However, even cured patients were suddenly forced to confront the possibility of death as a real threat. Even after successful treatment, it takes years before sufferers can be relatively certain that they are truly cured. Moreover, latent and long-term side effects of therapy can be serious. Here, one patient, a 15-year-old relative and a pediatric oncologist speak on their experiences of the process of being cured and of healing from cancer.

Christina Mermillod-Erbertz

(born 1973)

- Writer and social counselor at the Krebsberatung e.V. Berlin

- Developed colorectal cancer at the age of 42

Stella Mermillod

(born 2007)

- Student

- Was seven years old when her mother was diagnosed with cancer

Sabine Ehrig

(born 1964)

- Mother of three sons

- Developed bone marrow cancer at the age of 42

Prof. Dr. Angelika Eggert

(born 1967)

- Director of the Clinic for Pediatrics with a focus on Oncology and Hematology (Charité)

- University professor with research focus on neuroblastoma

Living with cancer

At the beginning of the 20th century, doctors dreamed of defeating cancer. They wanted to cure cancer at any cost; side effects and long-term consequences of the treatments often seemed secondary. Since then, the goals have changed. If the physical cost of a possible cure is too high or if the disease is too far gone, oncologists instead use treatments to transform cancer into more of a chronic illness: tailored therapies are used to prolong one’s life with cancer and to maintain the best quality of life possible. The interviews presented here provide insight into living with cancer and discuss today’s trends in cancer therapy.

Prof. Dr. Ulrich Keilholz

(born 1957)

- Oncologist, Hematologist

- Director of the Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center

PD Dr. Ute Goerling

(born 1965)

- Graduate psychologist

- Head of psycho-oncology at the Charité Comprehensive Cancer Center

Alfred Engel

(born 1962)

- Lawyer

- Has been living with the diagnosis of multiple myeloma since 2013

Perrin Akcinar

(born 1976)

- Certified pedagogist, psycho-oncologist, hospice companion

- Advises people sufferving from cancer and their relatives in Turkish at the Berliner Krebsgesellschaft e.V.

Stephanie Stegen

(born 1969)

- Pediatric nurse

- comes from a high-risk family: her grandmother, mother, cousin and great-aunt all developed breast cancer; at the age of 41, Stephanie Stegen received the same diagnosis

Dying of cancer

In 2020, Germany saw 239,600 cancer-related deaths. For most of these people, their life ended in a hospital; about one quarter of them died at home and 12 percent in a hospice care center. They each experienced the transition from life to death in their own unique way. How they experienced it depended on several factors: the place where they died, the people who provided them with medical care and emotional support, their attitude towards life and death, their faith, their worldview, and the nature of their illness. In the interviews shown here, people who have accompanied a cancer patient in the last phase of their life, including those who do so on a daily basis, talk about their personal experiences with dying.

Jutta Mätzig

(born 1968)

- Nurse

- Works in the Ricam Hospice, the first fully inpatient hospice in Berlin, founded in 1998

Prof. Dr. Angelika Eggert

(born 1967)

- As an oncologist, she also treats seriously ill children and adolescents.

Bernd Haselsteiner

(born 1951)

- Retired engineer

- At the age of 48, his wife died of cancer.

Perrin Akcinar

(born 1976)

- Psycho-oncologist at the Berliner Krebsgesellschaft e. V.

- Also accompanies seriously ill cancer patients with a German-Turkish history and their relatives

Imprint

The virtual exhibition “There’s something there: Cancer and emotions” is based on the exhibition of the same name, which will be shown at the Berlin Museum of Medical History at the Charité from July 2023 to January 2024. The exhibition was conceived in close collaboration between Bettina Hitzer, Anne Schmidt and Thomas Schnalke.

Project management and curation

Anne Schmidt

Design concept

e o t . essays on typography Lilla Hinrichs + Anna Sartorius

Programming

Supercomputer

Interview production

astfilm production Detlef Fluch Anne Schmidt

Portrait drawings

Klemens Kühn

Editing

Elke Jezler

Translations

Katie Meyer

Picture credits for the chapter photographs

Fig. 1: Unbekannter Fotograf, Schausammlung des Deutschen Hygienemuseums, Abteilung „Kampf dem Krebs“, 1930

Deutsches Hygienemuseum Dresden

Fig. 2: Orlando, Inkblot Test, 1950

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Fig. 3: Heritage Images, A man consults a Rowntree Doctor in his surgery, 1955

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Fig. 4: Unbekannter Fotograf, Chirurgische Polyklinik, Eingang Langenbeckhaus, undatiert

Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin der Charité, Berlin

Fig. 5: Unbekannter Fotograf, Aseptischer Operationssaal, 1910

Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und Ethik in der Medizin der Charité, Berlin

Fig. 6: Unbekannter Fotograf, Bestrahlung eines Portio-Carcinoms mit Symmetrie-Instrumentarium, 1918

Siemens Healthineers Historical Institute, Erlangen

Fig. 7: Klaus Mehner, Medikamententests der Pharmaindustrie an DDR-Patienten, 1990

Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur

Fig. 8: Set photo at the interviews, 2023

photo: Daniel Ast

Thanks to:

Perrin Akcinar, Dr. Asita Behzadi, Prof. Dr. Angelika Eggert, Sabine Ehrig, Alfred Engel, Dr. Ute Goerling, Bernd Haselsteiner, Prof. Dr. Ulrich Keilholz, Barbara Kempf, Jutta Mätzig, Christina Mermillod, Stella Mermillod, Matthias Minhöfer, Stephanie Stegen, Christina Zück.

Special thanks to the staff of the Library & Collection Medical Humanities at the Institute for the History of Medicine and Ethics in Medicine at the Charité for their support in image research and for the comprehensive provision of image material.

Copy-Right

We have made every effort to clarify the rights for the texts, photographs and films used here. In some cases, despite intensive research, we have been unable to identify or contact the rights holder. Anyone who may have a claim to such rights is kindly requested to notify us.

The exhibition was sponsored by:

The virtual exhibition was sponsored by:

Anbieter

Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Ausführende Institution: Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Zentrale Postanschrift: Charitéplatz 1, 10117 Berlin ->Campi der Charité

Die Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin ist eine Körperschaft des Öffentlichen Rechts. Sie wird durch den Vorstandsvorsitzenden gesetzlich vertreten.

Kontakt

Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité

Charitéplatz 1, D 10117 Berlin Tel.: +49 30 450-536156 Fax: +49 30 450-536905 ->BMM bei Facebook

Verantwortlicher im Sinne des Medienrechts

Prof. Dr. Heyo Kroemer, der Vorstandsvorsitzende der Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Verantwortlich für den Inhalt nach § 55 Abs. 2 RStV

Prof. Dr. Thomas Schnalke, Direktor des Berliner Medizinhistorischen Museums der Charité Tel.: +49 30 450-536122 Fax: +49 30 450-536905 E-Mail: thomas.schnalke@charite.de

Zuständige Aufsichtsbehörde

Der Regierende Bürgermeister von Berlin - inkl. Wissenschaft und Forschung Kontakt: ->Link

Senatsverwaltung für Gesundheit, Pflege und Gleichstellung Kontakt: ->Link

Umsatzsteuer-Identifikationsnummer: DE 228847810

Hinweis nach § 36 Abs. 1 VSBG

Hinweis nach § 36 Abs. 1 VSBG: Die Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin ist nicht verpflichtet, an einem Streitbeilegungsverfahren vor einer Verbraucherschlichtungsstelle nach dem Verbraucherstreitbeilegungsgesetz (VSBG) teilzunehmen. Sie erklärt sich nicht zur generellen Teilnahme an Streitbeilegungsverfahren vor Verbraucherschlichtungsstellen im Sinne von § 36 Abs. 1 Verbraucherstreitbeilegungsgesetz (VSBG) bereit.

Webmaster

Teresa Steffens Tel.: +49 30 450 536 143 E-Mail: teresa.steffens@charite.de

Haftung für Inhalte

Die Inhalte unserer Seiten wurden mit größter Sorgfalt erstellt. Für die Richtigkeit, Vollständigkeit und Aktualität der Inhalte können wir jedoch keine Gewähr übernehmen. Als Diensteanbieter sind wir gemäß § 7 Abs. 1 TMG für eigene Inhalte auf diesen Seiten nach den allgemeinen Gesetzen verantwortlich. Nach §§ 8 bis 10 TMG sind wir als Diensteanbieter jedoch nicht verpflichtet, übermittelte oder gespeicherte fremde Informationen zu überwachen oder nach Umständen zu forschen, die auf eine rechtswidrige Tätigkeit hinweisen. Verpflichtungen zur Entfernung oder Sperrung der Nutzung von Informationen nach den allgemeinen Gesetzen bleiben hiervon unberührt. Eine diesbezügliche Haftung ist jedoch erst ab dem Zeitpunkt der Kenntnis einer konkreten Rechtsverletzung möglich. Bei bekannt werden von entsprechenden Rechtsverletzungen werden wir diese Inhalte umgehend entfernen.

Disclaimer

Haftung für Links

Unser Angebot enthält Links zu externen Webseiten Dritter, auf deren Inhalte wir keinen Einfluss haben. Deshalb können wir für diese fremden Inhalte auch keine Gewähr übernehmen. Für die Inhalte der verlinkten Seiten ist stets der jeweilige Anbieter oder Betreiber der Seiten verantwortlich. Die verlinkten Seiten wurden zum Zeitpunkt der Verlinkung auf mögliche Rechtsverstöße überprüft. Rechtswidrige Inhalte waren zum Zeitpunkt der Verlinkung nicht erkennbar. Eine permanente inhaltliche Kontrolle der verlinkten Seiten ist jedoch ohne konkrete Anhaltspunkte einer Rechtsverletzung nicht zumutbar. Bei Bekanntwerden von Rechtsverletzungen werden wir derartige Links umgehend entfernen.

Urheberrecht

Die durch die Seitenbetreiber erstellten Inhalte und Werke auf diesen Seiten unterliegen dem deutschen Urheberrecht. Beiträge Dritter sind als solche gekennzeichnet. Die Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und jede Art der Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtes bedürfen der schriftlichen Zustimmung des jeweiligen Autors bzw. Erstellers. Downloads und Kopien dieser Seite sind nur für den privaten, nicht kommerziellen Gebrauch gestattet. Die Betreiber der Seiten sind bemüht, stets die Urheberrechte anderer zu beachten bzw. auf selbst erstellte sowie lizenzfreie Werke zurückzugreifen.

Diese Webseite verwendetet keine Cookies und Dienste anderer Webseiten.

Weitere Informationen zum Datenschutz erhalten Sie hier: Datenschutz der Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin Charitéplatz 1, 10117 Berlin Tel: +49 30 450 580 016 E-Mail: datenschutz@charite.de URL: ->Datenschutzerklärung